The Importance of Play for Children

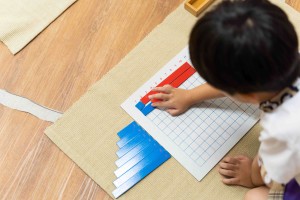

We have been talking a lot about the concept of ‘play’ and ‘playing’, and this is because in essence, children learn through play. Dr. Maria Montessori said, “He [the child] does it with his hands, by experience, first in play and then through work. The hands are the instruments of man’s intelligence.” Play should come from a child’s imagination and there is no right or wrong way to play – it could be anything, whether chasing after a butterfly, playing with board games or simply staring out a window. Play enables children to explore and make sense of the world around them, as well as to use and develop their imagination and creativity. Play is how children learn about the world, themselves, and one another. 4 Beautiful Locations Islandwide At House on the Hill, we strive to embody the true Montessori method and philosophy in every lesson and activity. Book A Tour In his book You Are Special: Words of Wisdom for All Ages from a Beloved Neighbor, Fred Roger wrote that “Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning. But for children, play is serious learning.” Adults need to be reminded that play does not need to be purposefully created. Play can occur naturally through the child’s imagination. For example, a child who is walking to a destination may stop along the way to observe their surroundings and chase after birds on the street. “Play is the work of a child” -Dr. Maria Montessori How We Play At House on the Hill It follows that at House on the Hill, we are playing all the time. Children’s development is stimulated through multi-sensory exploration where they learn to explore the world around them through their senses. In the prepared environment of a Montessori classroom, children learn and play at the same time. There are hands-on learning opportunities through practical life activities, from transferring objects with their hands and pouring water through a funnel to cutting short snip fringe and threading beads. We also have sensorial materials such as the Pink Tower and Knobbed Cylinders that help refine a child’s visual sense by learning differences in dimension. Such skills can also aid in their Mathematics learning in the years ahead. Such activities may seem frivolous to adults but it’s an important playtime for children. Here we see a child experiencing hands-on learning during our March holiday programme theme on “Bubbles” , where the children used recycled materials like bottles and socks to create items such as a snake bubble. At House on the Hill, we provide natural resources for child directed play as well. Our daily programming includes lots of time outdoors, in nature and the opportunity to learn through play in the sunshine. Our schools have mud or outdoor kitchens for the Playgroup and Pre-Nursery children and “Loose Part Play” for the Nursery and Kindergarten children. This is a great way to encourage them to exercise creativity during outdoor playtime. Through pretend play, the children will stay engaged and start seeing endless possibilities with their imagination. Dr. Maria Montessori once said that “The hands are the instrument of a man’s intelligence.” This coming weekend, do not hesitate to play! Do not be stressed about how you should plan an eventful day of play . Ask your child, how should we play today and you never know what creative ideas they will come up with. Have a jolly good time playing!